The founder of modern management, Peter Drucker, is usually credited with the adage

What gets measured gets managed.

From my previous experience in optimization I’m wary that measuring, even if a seemingly good metric, could be problematic in terms of unintended consequences.

It isn’t, however, an excuse to continue to optimize poor metrics. This is something that humans are very good at: finding better ways to accomplish a goal that is tangential to what we really want. And to a certain extent free market capitalism is predicated on the lowest cost producer finding better ways to lower costs and win the supply for a given demand.

This model seems to work efficiently until the the costs aren’t obvious, or collectively smaller than the individualistic gain (known as the Tragedy of the Commons dilemma.)

Under such a system the burden of information gathering largely shifts to the consumer. Not only does this take time, but it opens the door to misinformation. Of course, there are entities such as the FDA that aim to protect the consumer from harmful health affects, but it seems like the reach of such organizations can only go so far. Take, for example, 2 in 1 shampoo products which contain harmful sulfates for hair health. The value proposition here seems to be temporary dandruff relief and the convenience and time saved by combining shampoo and conditioner, at the expense of long term hair health.

But I suspect not every customer understands this trade off. The benefit of job specification is that not everyone should need to be an expert in hair care, but rather understand very well their segment of the economy. And this is only going to continue as jobs are further specified. So how do you protect the consumer? Should the FDA step in here? Or should in theory such products be efficiently replaced in the market?

Measuring this cost would surely change the demand for such products. ($5 per bottle + you may have oily hair more often.) For some people the tradeoff might be worth it. For others it provides helpful guidance to change their decision. And for still others who refuse to believe the extra information, it doesn't change their decision.

This argument extends beyond hair care. Currently governments are setting targets for their climate change goals which are expected to be met through a combination of public financing, subsidies, and improvements in infrastructure efficiency. .

Implicitly here, the goals are implemented in order to limit future damages and lives lost. So why not measure that? If the goal is to prevent climate related deaths, we could measure ‘X’ product in lives lost.

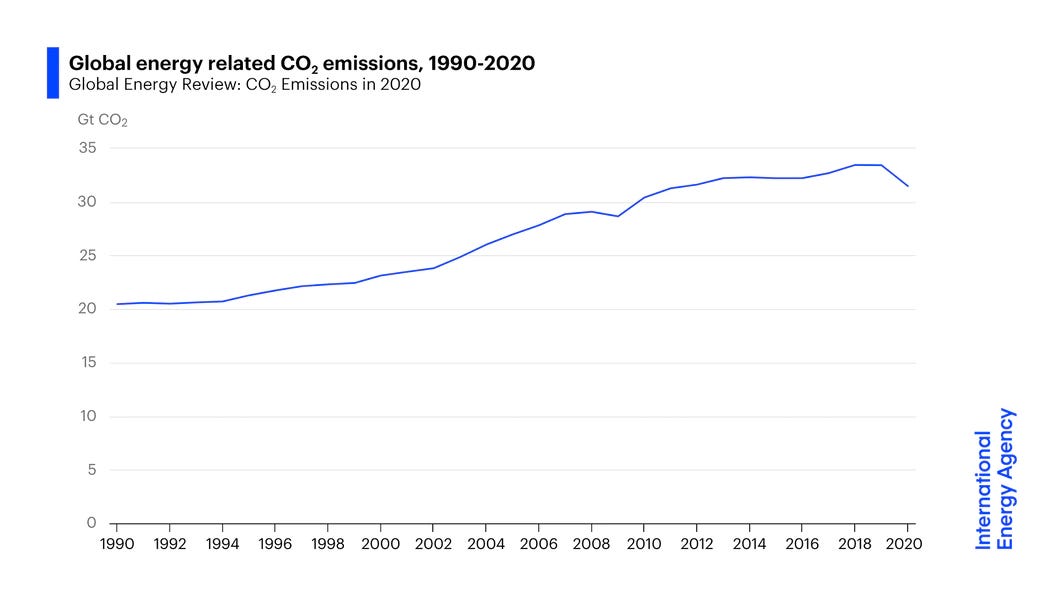

Take a crude calculation of the cost of a years worth of driving. The EPA estimates the average passenger vehicle emits 4.6 metric tons of CO2 per year, the WHO estimates 150,000 deaths are attributed to climate change per year, and from the above graph we might say 31 gigatons per year of CO2 is emitted. This equates to 2.2x10^-5 deaths per year per passenger vehicle. Of course this isn’t a very good estimate. It assumes that CO2 emissions directly cause each death, rather than potentially other climate phenomena.

The point being, a metric could be calculated, even if it is imperfect. Does this mean it should be used?

One could say that the role of government is to have a monopoly of the use of violence. Which, I suspect climate change could be considered violence, but maybe not. Would this metric potentially change decisions and help governments fulfill their role? Maybe, or maybe not.

What if the use of different metrics could lead to monopolies on certain products? (Imagine if Chevron produced less emissions than Exxon for the same priced gasoline.) Would it hurt the consumer in the end? Again, this argument assumes that businesses only care about profits and returns to shareholders (a very Friedman argument), but it doesn’t need to.

Other metrics could be managed.

Well said. Similar to the passenger car example you described, I think a number of related metrics will be relevant to the electricity grid as it goes through its transition. For example - cryptocurrency mined near a wind farm on 100% renewable electricity could be compared to the relatively “lethal” crypto mined on a coal-powered grid. The challenge with climate action is balancing our favorite metric (costs, or supply vs demand) with other important metrics like you mentioned, and meeting the highest-valued (by multiple metrics) demand

This was an awesome way to frame the implicit trade-offs governments are making on key policies that effect us all. I loved the analogy with shampoo 2 in 1 to explain a pretty complex topic. Well done and looking forward to more!