The first economics class I took in college was macroeconomics 104H. It was held on the second floor of an old and dusty Penn State University classroom with a great view of the blossoming maple trees. We learned about Lagrangian utility optimization, a grad level technique involving partially differentiated equations. I know it is grad level since I re-learned Lagrangian utility optimization in my own graduate program 4 years later. My professor may have been a little enthusiastic about teaching honors kids. He used to roll a piece of chalk lengthwise in the palm of his outstretched right hand, left hand either tucked behind his back or toying with his glasses, as he carefully considered our questions on the lecture.

One day in class we were assigned to read a printed out passage from the New York Times Magazine. It is a fabulous article on the High-G.D.P. man, and the Low-G.D.P. man linked here. I have taken a passage and pasted below:

Consider, for example, the lives of two people — let’s call them High-G.D.P. Man and Low-G.D.P. Man. High-G.D.P. Man has a long commute to work and drives an automobile that gets poor gas mileage, forcing him to spend a lot on fuel. The morning traffic and its stresses aren’t too good for his car (which he replaces every few years) or his cardiovascular health (which he treats with expensive pharmaceuticals and medical procedures). High-G.D.P. Man works hard, spends hard. He loves going to bars and restaurants, likes his flat-screen televisions and adores his big house, which he keeps at 71 degrees year round and protects with a state-of-the-art security system. High-G.D.P. Man and his wife pay for a sitter (for their kids) and a nursing home (for their aging parents). They don’t have time for housework, so they employ a full-time housekeeper. They don’t have time to cook much, so they usually order in. They’re too busy to take long vacations.

As it happens, all those things — cooking, cleaning, home care, three-week vacations and so forth — are the kind of activity that keep Low-G.D.P. Man and his wife busy. High-G.D.P. Man likes his washer and dryer; Low-G.D.P. Man doesn’t mind hanging his laundry on the clothesline. High-G.D.P. Man buys bags of prewashed salad at the grocery store; Low-G.D.P. Man grows vegetables in his garden. When High-G.D.P. Man wants a book, he buys it; Low-G.D.P. Man checks it out of the library. When High-G.D.P. Man wants to get in shape, he joins a gym; Low-G.D.P. Man digs out an old pair of Nikes and runs through the neighborhood. On his morning commute, High-G.D.P. Man drives past Low-G.D.P. Man, who is walking to work in wrinkled khakis.

By economic measures, there’s no doubt High-G.D.P. Man is superior to Low-G.D.P. Man. His salary is higher, his expenditures are greater, his economic activity is more robust. You can even say that by modern standards High-G.D.P. Man is a bigger boon to his country. What we can’t really say for sure is whether his life is any better. In fact, there seem to be subtle indications that various “goods” that High-G.D.P. Man consumes should, as some economists put it, be characterized as “bads.” His alarm system at home probably isn’t such a good indicator of his personal security; given all the medical tests, his health care expenditures seem to be excessive. Moreover, the pollution from the traffic jams near his home, which signals that business is good at the local gas stations and auto shops, is very likely contributing to social and environmental ills. And we don’t know if High-G.D.P. Man is living beyond his means, so we can’t predict his future quality of life. For all we know, he could be living on borrowed time, just like a wildly overleveraged bank.

Herein lies a problem with GDP. By definition it is a measure of the economic activity in a country. Not necessarily the goodness of the country’s economy.

The problem relates to utility functions, or, what economists use to estimate relative happiness. Similar to another post considering utility functions, two of the most common forms consider logarithmically increasing returns, or Cobb Douglas returns for a set of goods.

U(x1,x2) = ln(x1)+ln(x2)

U(x1,x2) = x1^k * x2^1-k where 1 >= k >= 0

Where x1 and x2 are two different goods, and k is a constant between 1 and 0.

It makes sense to use logarithms or fractional exponents since both functions provide diminishing marginal returns to utility. The long studied phenomena that the next quantity of a good gives you less happiness than the previous (an inverse proportionality between marginal utility and a quantity of a good: dU/dx1 = 1/x1 so differentiating yields U(x1) = ln(x1) )

However, these functions are strictly increasing. And it seems from our story of the High-G.D.P. man that some goods eventually turn into “bads” either for himself or society in aggregate, which in turn affect him. Specifically here I’m thinking of his low MPG vehicle driving pollution and climate change. Can this “tipping point” where a good turns into a bad be incorporated into the model? And what happens when the tipping point depends on not only High-G.D.P man, but all the other members of society? (Hint: this is the Tragedy of the Commons!)

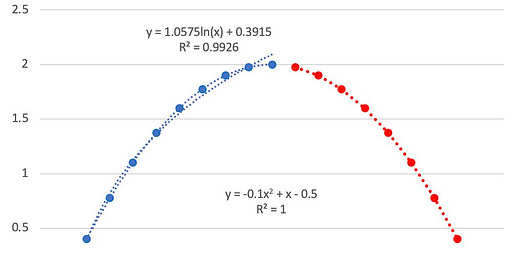

Here, I propose a parabolic fit. Note that on the blue side of the curve, a logarithmic fit seems right. It is strictly increasing and the marginal return decreases with increasing x. And if you’re only ever in the blue part of the graph, either model would work.

Considering a parabolic fit for these utility functions helps explain why GDP is a bad metric for standard of living. It manifests in common critiques of GDP that it doesn’t account for the environment, leisure, health, and inequality. So when there is news of slowing growth? I’m not too upset. Some better metrics might be unemployment rate (can people find a job?) inflation (can people buy things they want or need?) and investment (is there funding for long term improvements?) Growth can only be a helpful metric to a point.

Maybe I didn’t know it at the time, but this class, along with my research in game theory sparked my interest in economics. I recall at one of the (many) career fairs I had attended I was asked what my favorite class was. As a chemical engineering major talking to a firm that worked on hydraulic pipes, I knew what the answer should have been. Chemical engineering 100 baby! But I couldn’t get macroeconomics 104H out of my head. That interviewer unsurprisingly didn’t follow up.

So Professor Lamba, if you are reading this, thank you. Thank you for the class, and for helping spark my interest in economics.