Why a supply curve isn't positive and linear

I may not entirely agree with the traditional model

When I was living in Paris I lived above and frequented a cafe called “La Chope du Chateau Rouge.” This coffee shop by day, bar / restaurant by night was authentically Paris. I stopped by every morning for my 1 euro espresso, and on the weekends did my schoolwork on the terrace over a cafe au lait and some lunch. It was some of the best food I had in the entire city. As it was small and a bit off the beaten path in Montmartre, (the historically artistic neighborhood of Paris where Picasso, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Degas all either lived or worked), the menu rotated. So each day there were about 3-4 different plates you could choose to pair with your appetizer and dessert, recorded on two chalkboard easels located in the front and back of the cafe. The beauty of this setup was that you could come back frequently and experience what had inspired the chef that day, while the business optimized over either inventory or marketplace sales. And each day the price of a plate might vary slightly, which works out well for the chalkboard.

Changing prices is generally a difficult thing to do even if you don’t have a rotating menu. Consider the price of the espresso instead. As a seller of coffee I might eventually face the scenario of increasing cost of beans, milk, or labor, and wish to my prices from $3 per coffee average to $3.50 per coffee average one time instead of many, smaller price hikes ($3.01 on Monday, $3.04 on Tuesday, $3.05 on Wednesday, $3.10 on Thursday.)

Why is the one time larger price hike preferable than many, smaller hikes? Partially it may be due to marketing. For example the concept of prices ending in “99” come across as cheaper, as we’ve been conditioned to ignore the cents on the dollar. So a coffee might increase from $2.99 to $3.49 since, if we’re going to ignore the cents anyway, once you pass through the milestone of “$3.00” you might as well increase more as the cents on the dollar aren’t paid attention to very much.

Additionally many smaller hikes signal that there is no end in sight. In the example above I might anticipate that since prices are continually increasing then I might buy now to avoid paying the future higher price, which an increase in demand now would further drive inflation and continually spiral prices upwards. This is what happens in hyperinflation, a phenomenon of extreme price increases generally started by excessive government spending funded through printing currency. This is a very bad thing, as there is not stability in the market and often results in widespread poverty since wage increases are not able to keep up with price increases. Of course, this wouldn’t be a problem if wages were tied to the pace of inflation, but this might not be preferable for the business side in planning investments and hiring, and already occurs for social security benefits which are adjusted for inflation on the yearly basis… which are too infrequent to be effective.

Lastly, it takes work to update prices. This is traditionally called “Menu costs” or the costs associated with printing new menus for a restaurant when the prices change. Outside of the cost of paper, ink, and printing capacity associated with printing physical menus, there would still be a cost associated with updating the menu even if all of the prices were written on a chalkboard like at La Chope, or stored digitally and displayed on a screen. The cost then comes from knowing what new price you want to have. Doing the calculation of summing up fixed and variable costs, forecasting demand, and finding the intersection of where supply equals forecasted demand is nontrivial and time consuming.

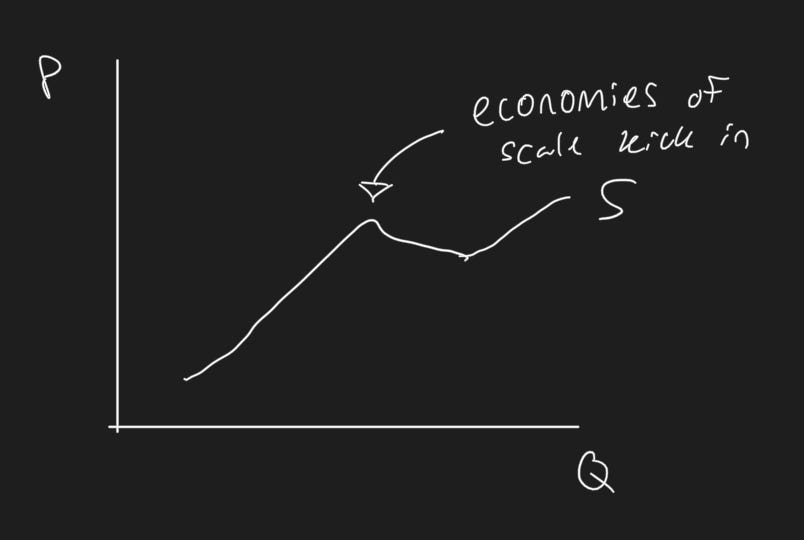

Since prices are sticky then, a supply curve might not exactly look like a straight line like you see in economics textbooks.

During periods of stickinesses you may be attempting to hire more workers, or buy a new machine, or increase productivity of your workers through competitions to sell more goods even though your prices are not changing.

Additionally, if at some point you face a trade off between hiring an additional laborer or substituting some of your laborers for a machine which makes fewer laborers more productive, there might be what is called economies of scale. In this instance, the machine enables production of more goods for a lesser cost.

Traditional theory teaches that when a machine is added for economies of scale this is equivalent to a “shift” of the supply curve. Such that a new technology enables you to produce more goods at a lower cost at every quantity.

I can see a couple problems with this model rather than the previous. For one, if you buy a new machine then why run it at a lower capacity than what you had previously?

Say you buy the machine with the goal of expanding production. This makes sense since it would be a way to substitute to a more efficient way to produce the same or more goods.

If you use the machine with the goal of producing less goods, then why not buy the machine to begin with? I can think of a couple reasons. One being that accessing capital can be difficult at times, and the other being that you are forecasting a decrease in the demand of your good (for example if you are an oil producer you might choose to automate production to achieve higher margins on your fewer goods.)

If this is the case and you are running at lower capacity, the machine is sitting idle at times and the unused capital costs could potentially outweigh the gains in efficiency. The curve then might shift but its slope might also shift:

Until a point where it would be better to pay for 1 laborer rather than 1 machine and no laborers.

Second, it misses the economies of scale argument. Unfortunately in real life it is hard to buy the exact quantities of goods to create each good you would like to sell. For example, you might be able to buy a bag of coffee beans but not the exact amount of beans to make one pot. In this instance then, it would surely cost less (per pot) to produce two pots of coffee than it would to produce one pot (and throw away the remaining ingredients. So at some point, the assumption of perfectly divisible goods just isn’t a great assumption to make and economies of scale do exist.

If you squint then, the supply curve looks like it should go up. This is straightforward microeconomics that to produce additional goods you have to hire a less productive worker (called diminishing marginal returns in econ jargon), but the shape of the upward might not be as simple as linear.

So, what does this mean? Over the course of the pandemic we’ve had shocks. Supply shocks due to increased difficulty of transporting things because people were sick, demand shocks as people stayed home and so they wanted more furniture and better videoconference software and Peletons, to now people want to travel and go back to their life in the city and go out to eat. As these later shocks have occurred, there has been a noticeable trend of too many dollars chasing too many goods (better known as inflation!) Hence, due to sticky prices and menu costs, businesses aren’t increasing prices from $3.00 to $3.01, but rather $3.00 to $3.50. This may be a contributing factor to the high rate of inflation we’re seeing now.

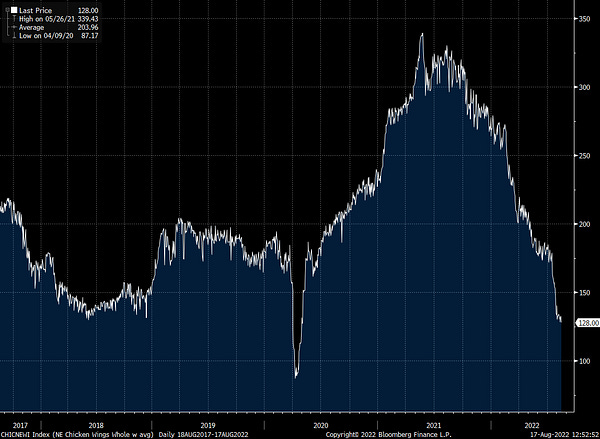

Additionally, as businesses respond to supply and demand shocks, they may become more efficient at producing goods, and economies of scale will tend to drive (real) prices down.

All of this is to say that the recent inflation figures (8.5% last month and 9.1% year over year) seem scary, but it might be reasonable to think that it will come back down to earth (the Federal Funds Rate target of 2%) besides the traditional reasons of the Fed raising interest rates, gasoline prices coming down, and falling chicken wing prices.